Did you read that Uncut Magazine recently rated the top 500 albums of the 70s and put Marquee Moon by Television in the top slot? Great album, I adore it. I’m all for it. But to me, it’s a weird choice for the best album of the 70s. Why? Because, while it was released in early 1977, it’s not really a 70s album. Well, not to me.

When we look at popular music and rock in particular, the least analytical but most telling aspect isn’t genre, or format, or style, but decade. Which decade a piece of music represents is the descriptor that really delivers because musical decades may be loosely defined, but they are multifaceted and freighted with implications and rich subtext. We like talking and thinking about music in terms of decades because it keeps the definitions loose and the vibes front and center.

The genre tag is helpful for marketers and merchandisers, but not for most listeners. Sure, there are people who keep it strict, metalheads, jazz nazis, bluegrass purists – but for the rest of us, the ability to cross state lines into any genre that may suit one’s fancy is what’s great about living in a free society, what’s enjoyable about being a music fan. But we are still human animals, subject to our primordial evolutionary impulses. That need to parse, categorize, analyze, and often reject is deeply rooted in our survival instincts. Where the soul just wants to dance, to experience without the need to analyze everything, the brain needs to organize and code and categorize. It’s our DNA as humans.

But here’s the thing. Cultural decades don’t follow strict guidelines, nor do they respect borders.

It’s been said that the 1960s ended a month early with the four killings at the concert at Altamont on December 6,1969 (and maybe it’s accurate to say the turbulent 60s started late too with the Cuban Missile Crisis in October ‘62). Despite a trove of Doo-Wop inspired songs that bled over from the 50s, the mad, volcano of constant change that was the musical decade of the 60s really begins with the arrival of the Beatles, the subsequent British Invasion, along with the emergence of Bob Dylan, James Brown, and the music of Motown, Stax, and Muscle Shoals – all starting around 1963, give or take a year. Towards the other end of the decade, many would argue that the mid-1968 release of the raw, woodsy Music From Big Pink by The Band slammed the door on the psychedelic movement in favor of simplicity and authenticity, signaling the end of what we think of as 60s rock music. Subsequent post-psychedelic 1968 releases, the Beatles’ White Album and Beggars Banquet by the Stones, plus the Byrds’ full-on country-rock Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and the 1969 debut Crosby, Stills, and Nash album are all evidence that music had drastically shifted to the new ethos long before the 1970s arrived.

The 90s too was a decade in rock that got an early start with proto-Alternative rockers Jane’s Addiction, the Pixies, and Sonic Youth hitting their stride around 1987-88, well before the official start of the decade. Likewise, green shoots of the 90s Alt-Country movement were showing in the mid-late 80s with bands like the Georgia Satellites, Jason and the Scorchers, and the Long Ryders. And the 90s revival of the folk-based singer-songwriter movement also began in the late 80s with artists like Tracy Chapman, Suzanne Vega, Billy Bragg, and ex-Plimsouls frontman Peter Case breaking with the more synthesized trends. Add the explosion of Hip Hop at the end of the decade and it’s easy to see that the arc of what we all think of as 80s music was losing steam and would not last all the way to the decade’s end. In the context of the highly stylized, commercialized, synth-based or hair-metal MTV-driven decade that was the 80s, these developments and innovations stood out as bands and artists wanting to move on to something new, grittier, looser, and more authentic.

All of this is to say that “which decade” works well for our categorizing minds but in no way should the numerical year in which a piece of music was released be considered to be determinative of anything useful. This is especially true with a particularly progressive form of music like rock.

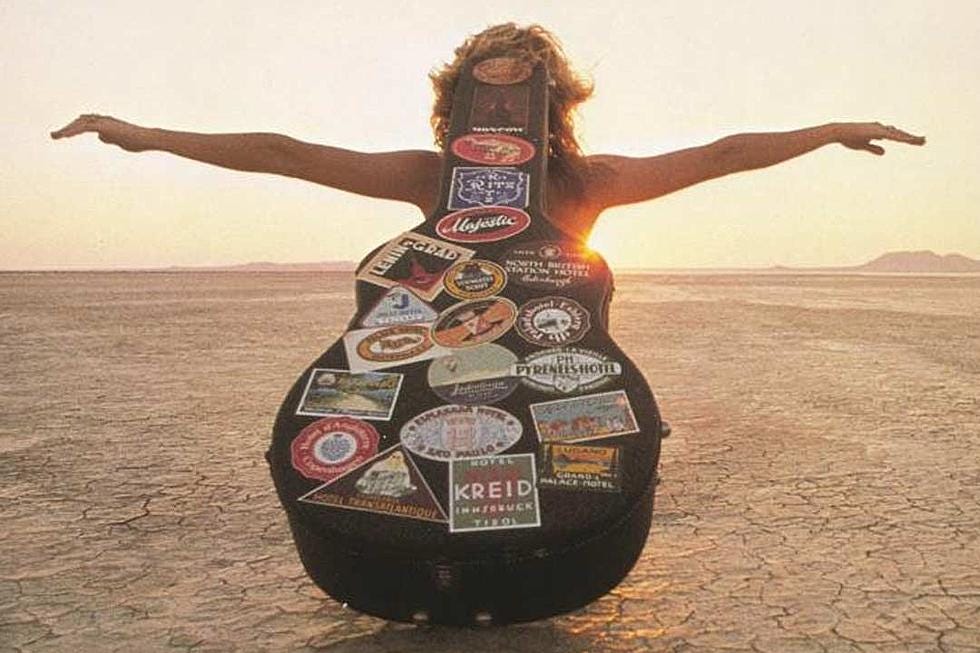

So, for fun, let’s see if we can build a timeline of rock music and its development in its golden age to see if we can create a construct for understanding what comes next. None of these “border years” should be taken too literally. They are meant as general landmarks.

1954-1962: Starting with the hits of Bill Haley’s Comets and Chuck Berry, the recorded history of rock and roll, what we think of as “50s music” can probably be traced back to 1954-55. Elvis Presley’s golden era stretches from 1954-1958 but then crosses over into the early 60s with popular ballads like “Are You Lonesome Tonight” and “I Can’t Help Falling In Love With You.” This is a pattern followed by many other early rock and roll luminaries, a creative explosion of high-energy bangers released in the mid-50s followed by a period of Country or Doo-Wop influenced ballads towards the end of the 50s and crossing over into the early 60s. Taking into account all of the development we know it will go through, it’s here with 50s music that we can see rock and roll growing from its infancy through its full-fledged childhood.

1963-1968: The arrival of the Beatles and Bob Dylan signaled the beginning of the 60s, a period of explosive change, development, and transformation where “rock and roll” would mature musically and lyrically into “rock” (it’s my opinion that that occurs in 1965 with Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home album, but that’s just one theory). In this period, we see exponential album-to-album growth among the British Invasion bands, as well as American groups like the Beach Boys, Simon and Garfunkel, The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield, the San Francisco groups like Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, and the Grateful Dead, a period of insane development cresting with the ornate psychedelic movement that permeates pop, hard rock, and even folk-rock. As stated earlier, that all comes crashing to an abrupt halt with Music From Big Pink in favor of a grittier, funkier approach that clearly points the way to the 70s, where rock will come of age and hit its full maturation. In this way, I like to think of this ever-shifting era of incredible growth, 1963-1968, the heart of 60s music, as rock’s adolescence.

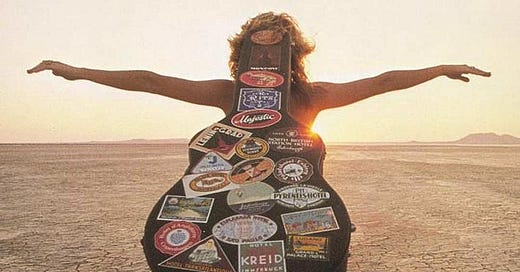

1969-1976: It’s here where rock music comes into its own, feels its oats, and by marrying with more and more refined technology, splinters into about 20 different sub-genres from hard rock to yacht rock and everything in between. It’s a decade marked by diversification, refinement, and overt musicality; Steely Dan and Chicago are bands that could have only happened in the 70s, but that could be said of so many bands. The time when overblown prog bands like Yes, ELP, and Genesis roamed the earth, but it’s also where rock norms were established, where most of what is now programmed on Classic Rock radio was made, an aesthetic that can be thought of as peaking with albums like Boston and Rumours, both released in 1976. It’s also when high-quality transistorized, large-scale recording consoles, 24-track technology and noise reduction become commonplace in studios, fostering the trend of craft and slickness substituting for raw artistry and inspiration. Big business enters the picture in earnest in the 70s, mounting stadium-sized concert tours on a massive scale with impressive light shows and other onstage theatricality. It’s a decade that starts with an overt embrace of authenticity and stripping back of artifice that ends in an orgy of rock bombast, self-glorification, limos, private jets, mountains of cocaine, and massive corporate profits.

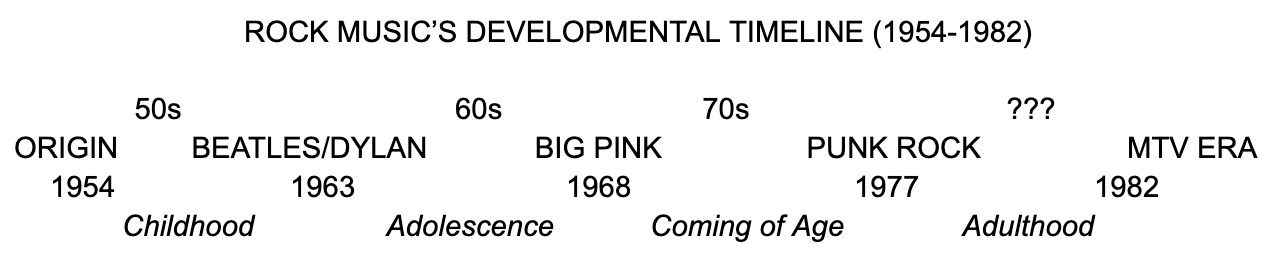

1977: Enter the Sex Pistols and punk rock. Punk was a cataclysmic event that overtook the rock world like an eclipse, like a pandemic. And like a pandemic, it exposed the fundamental flaws of a system propped up by an expired set of myths and a faulty, weak ethos. As a vicious send-up of rock’s bloat and hollow pageantry, punk amounted to nothing short of a paradigm shift, not so much for rock fans, but for aging, jet-setting rock stars who were sent running scared, feeling they had to quickly regroup. The Sex Pistols may not have outsold Pink Floyd, but punk stabbed deeply into rock’s existing power structure and norms, which were gaining strength and consolidating all through the 70s. It created an instant, existential identity crisis among rock’s ruling class, the effects of which were foundational and lasting. It’s true that rock was never the same again after 1977.

Which brings me to my main point. The next era in rock music (vaguely defined), starts as an elemental reaction to the punk revolution and lasts for years. A period of essential looseness, of stylistic and economic democratization marked by intense musical experimentation that persists until the beginning of the strict, essentially dictatorial reign of MTV. Let’s call it 1978-1982. A chaotic explosion of creativity in a time where the status quo had expired and no new rules were yet established, this adventurous period in rock signified more than a new sound, or a “new wave,” these 4-5 years constituted, I maintain, a new decade.

In its short, 4-5 span, the New Decade constitutes the muffin top of rock’s development. It’s a time where the art form is finally self-aware and self-referential, where it can pivot back to any point along its own timeline or reach out into the future in search of new ideas. It’s a period of lost innocence, powered by sophistication and savvy, the New Decade is where rock enters the adventure of full adulthood and, for the open-minded rock fans who lived through it, the experience was head-spinning.

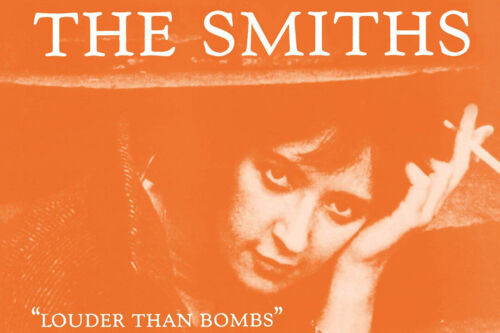

Pub Rock (Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, Squeeze), Goth (The Cure, Bauhaus, Siouxsee and the Banshees), Two-Tone (English Beat, Madness, The Specials), New Wave (Talking Heads, Devo), Post-Punk (Echo and the Bunnymen, Psychedelic Furs, U2), Art Rock (Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Thomas Dolby), Power Pop (Cheap Trick, The Knack), Brutalism (Joy Division, Public Image Ltd.), Synth Pop (Depeche Mode, Eurhythmics, Human League), College Rock (R.E.M., The Smiths) and punk-informed bands like The Replacements, Husker Du, Minutemen, Gang of Four, Pretenders, and The Police were cropping up all over the place in this fertile period. Even mainstream rock radio was deeply affected by the post-punk paradigm shift with breakout bands like The Cars pointing the way forward and major artists following suit stylistically (listen to ELO’s “Don’t Bring Me Down” as one example). Bruce Springsteen stripped back his cinematic Born to Run approach for Darkness on the Edge of Town while Billy Joel toughened up his sound on Glass Houses, both albums roundly acknowledged to be influenced by punk. Even Van Halen, who emerged as a sort of rock and roll second coming with guitar demigod Eddie Van Halen and the paragon of excess David Lee Roth out front, despite breaking out with their self-titled debut in 1978, were examples of the new phenomenon. Van Halen deconstructed rock norms and represented the same post-70s paradigm shift in their own colorful way. Everywhere you looked, it was clear that we rock fans were not in Kansas (Styx, REO Speedwagon, or Boston) anymore.

Take David Bowie. Tracing the output of 70s rock’s shape-shifting avatar of change through this period can serve as a road map of the New Decade. Bowie’s Berlin Trio (Low, Heroes, and Lodger) plus his culminating work Scary Monsters (and Super Freaks) represent his lofty peak (1977-1980) as an Art Rock pathfinder and trendsetter. After this innovative 4-album burst, Bowie took a long break where he took time off to act in various films and on Broadway in The Elephant Man, to strike a new lucrative record deal with EMI Records, and to contemplate his next move in terms of musical output. When Bowie reemerged as a musical act, it was in 1983 during the steep ascendancy of MTV with the glossy, overtly commercial 80s-music prototype Let’s Dance, an appealing, contemporary album that constituted an about-face as a dedicated artist, clearly signifying the newly minted 80s era and signaling how 70s rock heroes were to fit themselves into it.

Similarly, by the time The Police released their final album as a group in 1983, they were worlds away from the punk-inspired trio that crashed onto the scene in 1977 with the Outlandos d’Amour and the immediacy of their edgy, incredibly fresh 1-2 punch of “I Can’t Stand Losing You” and “Roxanne.” Where Synchronicity was essentially an MTV star turn for their camera-ready singer Sting, The Police spent the period of the New Decade as an adventure-driven democracy that featured all three principles, Sting’s basslines plus strong melodies and vocals in perfect balance with Andy Strummer’s innovative guitar parts and Stewart Copeland’s insanely energetic, reggae-influenced drumming. Over the course of five albums, the band got progressively more and more popular, garnered bigger recording budgets, became more polished and refined (and success-oriented), distancing themselves further and further from the punk ethos that spawn them, until they embodied the normative opulent 80s ultra-pop sound of the MTV era with mega hits like “Every Breath You Take” and “King of Pain.” Out of chaos, order. Nature abhors a vacuum. Money changes everything.

Now take Roxy Music, a band that was way ahead of their time embodying the post-70s New Decade ethos and sound since their debut album way back in 1972, breaking ground that New Decade luminaries Television and The Cars would build upon in 1977-1978. Roxy Music’s initial five-record span ended with the stunning Siren album (1975) and the elegantly piquant single “Love Is a Drug,” but they would return strong after an extended hiatus in 1979 with a three-album run that culminated with their sublime Avalon swan song album in 1981. As dominant as they were in the New Decade where they essentially launched the New Romantic style that would later influence 80s bands Duran Duran, Simple Minds, Spandau Ballet, and Culture Club among others, Roxy Music were clearly New Decade since their inception. So it goes with decades.

While many other 60s and 70s heroes lost the plot in the post-punk era, some like Pete Townshend, Ray Davies, Paul Simon, and King Crimson rose to the challenge with some of the most risky, inspired music of their careers. The Stones released their post-punk statement, Some Girls in 1978. And Bob Dylan responded with his all-time most punk statement by going Christian at this time, delivering three gospel releases and following them with the sinewy Infidels album backed by the acclaimed reggae rhythm section of Sly and Robbie. It was a wild time.

Small independent labels like Sire, IRS, SST, Stiff, and Twin Tone, were as New Decade as the bands and artists they championed. Unlike the eras that immediately preceded or followed, this was a period where the currency was originality, where for a moment, sales took a backseat to innovation and ideas. A rare, exciting time in the history of rock, and most importantly, it was an era chock-full of stunningly great, adventurous music displaying a seemingly infinite amount of variety.

So, if you’re still with me, you might be asking yourself, “OK, New Decade, yeah, but so what… why is it important?”

Consider where this New Decade falls in the timeline of rock. It’s a period of democratization, wild experimentation, and steep psychic growth sandwiched between two eras (tail of the 70s expansion and the rise of MTV) that were dominated by strict, consolidated power structures and conservative musical trends. As such, it’s not only inaccurate, but downright unjust to allow the early albums of The Police or Talking Heads to merely be tagged as 70s music, just as it’s stylistically wrong to label Imperial Bedroom or Sandinista! 80s music, despite these works’ literal chronology. It doesn’t serve anyone to let these vagaries continue so let’s carve out some mental space for a new term, whether we use it or not. By doing so, we can keep the integrity of all of these categories and get on with the real business of enjoying the music.

Afterthought: I was listening to one of my favorite podcasts this morning, the Slate Political Gabfest, and one of the hosts, Emily Bazelon, the legal expert who teaches at Yale and writes for the New York Times was asked at the end what her cocktail chatter was for the week. Breaking from her usual erudite fare, she spoke about listening to one of her own favorite podcasts, this one is engaged in a new series discussing finales of beloved TV shows. She said something that struck a chord with me and, if you’re still reading, will likely do the same for you. She described her podcast as one of “low stakes and high passions,” something she apparently loves as much as I do. And to quote another podcaster, my wild, over-analyzing friend Dave Gebroe host of the top-rated podcast for musical obsessives, Discograffiti, who at the end of a long exchange we had about some rabbit hole of rock minutia, texted, we gotta get it right because “THIS SHIT IS IMPORTANT.”