I was a music major in college but my favorite course was Art History. I loved learning about the various schools of art through the centuries, why they arose, privately choosing my favorites. Nerd that I am, I relished the opportunity to be able to identify works of art and the artists who created them. I took Music History too (a lot of it, I had to for my degree), but I found that whole pursuit of studying the history of “serious” music to be so academic. I grooved much more deeply comparing the artists of the Renaissance to the Age of Reason, and then onto modernity, how they were affected by the shifts in society around them, and how it came out in their art. I only took one survey course, Art History 101, but it left its mark on me.

Immediate side note: at our wedding reception, my wife and I thought it would be an amusing game to include the name of a painter on each guest’s seating card and let them find their table which was marked with the postcard of their famous painting. Plus we figured it would set a playful, artsy-nerdy tone for the event. We figured it would be fun for people to mingle and solve the puzzles together. Some people were genuinely pissed, I guess. That’s what we were told a few weeks later when it was a safe enough distance that we might laugh about it.

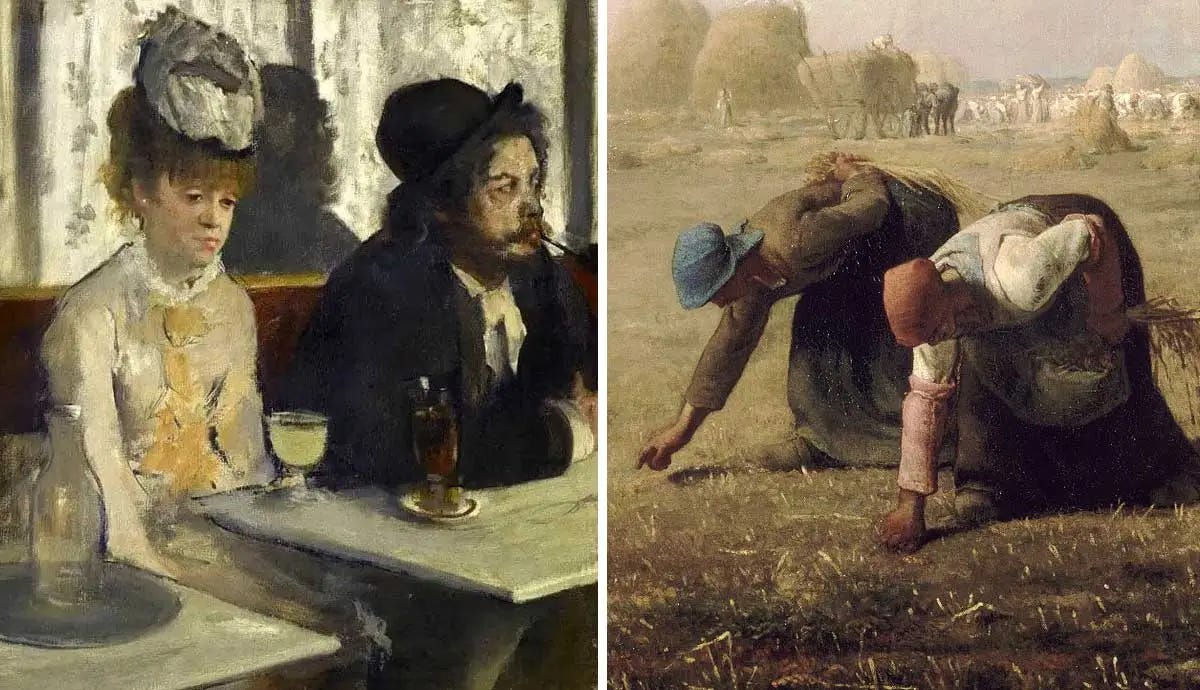

Zooming in on the 19th Century, things get interesting in art history. In the early part of the mid-1800s in France, a movement emerges called Realism that rejects the sweeping, mythic imagery of Goya, Delacroix, and the previous Romantic movement in favor of gritty, real-life scenes of peasants engaged in normal life and politically charged depictions of events meant to evoke a specific response to injustice.

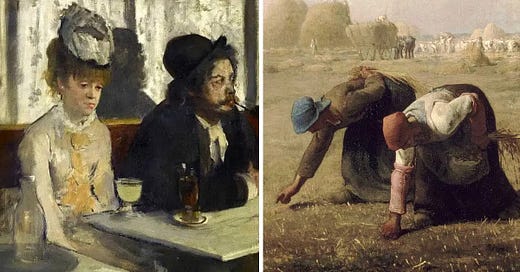

The next generation of French painters rebelled against the Realists though, their precise brush strokes, their attention to detail, and the dark, literal nature of their treatment of subject matter in favor of a light, airy approach to painting and a much more abstract treatment of subject matter (often the point of the painting was merely light, color, and pure emotion). These were the Impressionists of the late 1800s who were thought of as crazy radicals in their time but emerged and endured as the popular favorites of millions of art lovers.

Back to music. Did you see this year’s Grammys? Wasn’t Joni Mitchell’s performance just spellbinding? I was hanging on her every word, each lyric resonating with shifted meaning now that she is back from her long recuperation from a life-threatening brain aneurysm. “Both Sides Now,” indeed. I have loved Joni’s music so deeply for so long, feared for her health, and watching her encircled with the love of fellow musicians and singing voices was a poignant and emotional experience I won’t soon forget.

The other astonishing performance of the night was Tracy Chapman’s duet with country star Luke Combs who has had a hit this year across multiple charts covering her song from the late 80s, “Fast Car.” Combs has said that he wanted to cover “Fast Car” because he so fondly remembers being a kid driving with his dad, who was a big fan of the song. Their blend on the song and its specific lyrics provided more than just great music. It’s a very literal song about striving to rise out of poverty to scratch out a bit of success and personal pride against the odds. That they are not only different races, but potentially represent different sides of the political divide at a fragile moment in modern America, finding commonality in this story had a lot of resonance for me and, I suspect, for a lot of others watching. Common ground is hard to come by these days. I don’t know if they planned it that way, but I was moved.

But what I really wanted to talk about is something I’ve been thinking about for decades now, brought to light when I heard these two songs side by side at this year’s Grammys. Now, as unlikely as it may seem, there are people who don’t have names who get super-annoyed with me when I get too analytical about songwriting, but I wanted to share my thoughts, so feel free to look away at this point. You have been warned.

Early in my last Substack, “A New Decade,” I mentioned the songs of Tracy Chapman while discussing the late 80s rebirth of the singer-songwriter movement (my point there was that this was an early onset of what was to become a substantial 90s music movement). What I didn’t talk about is how the songwriting of that new singer-songwriter movement later developed through subsequent years into a unique art form that may have been inspired in part by the trailblazers of the 60s and 70s, but turned out to be rooted in its own, significantly different approach to lyric writing in songs. That new movement, in my view, never ended; Taylor Swift is the latest iteration of a lyric writing style and approach that started small in the late 80s with Suzanne Vega and Tracy Chapman and exploded in the 90s with songwriters as diverse as Lisa Loeb to Liz Phair to Alanis Morissette, through the ultrapop songs of the boy bands and Britney Spears, though Emo bands, and on through the pop stars of 2010s and 2020s. It is a phenomenon that has endured to the point that we no longer should think of it as a trend, but as a school, the school of Lyrical Realism. And it’s interesting to view it in contrast of the songwriters of the previous era Dylan, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Lennon-McCartney, Neil Young, and Joni Mitchell to name a few leaders in the field, who comprise what we can probably think of as more than a trend, but a school too, the school of Lyrical Impressionism.

This is the point in the article where I offer disclaimers. I am using broad strokes to talk about over-arching ideas. I do not pretend to know every song written by the artists I cite. Nor do I claim that every major artist within these eras falls squarely or even vaguely into these schools. For instance, I do not consider Lou Reed’s songs to be very impressionistic, nor do I think of Sarah McLachlan as being much of a lyrical realist, if at all. I know the impulse to try to refute and rebut is strong but please hear me out.

You got a fast car

I want a ticket to anywhere

Maybe we make a deal

Maybe together we can get somewhere

Any place is better

Starting from zero, got nothing to lose

Maybe we'll make somethin'

Me, myself, I got nothing to prove

If we examine the lyrics of Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car,” we can find it to be a fine example of realism in songwriting, in that there is no use of figurative language anywhere in the song. It’s vividly real from start to finish, what the main character is experiencing, remembering, and aspiring to. And while the elements of poetry are here in full force, meter, rhythm, diction, strong imagery – it’s not a song that relies heavily on poetics, metaphors, or the listener’s interpretation. Almost like journalism, “Fast Car” is a plain and powerful view into the character's world, their experiences, their hopes and dreams, and misgivings. Lyrical realism at its most effective.

Rows and flows of angel hair

And ice cream castles in the air

And feather canyons everywhere

I’ve looked at clouds that way

But now they only block the sun

They rain and they snow on everyone

So many things I would have done

But clouds got in my way

I've looked at clouds from both sides now

From up and down and still somehow

It's cloud illusions I recall

I really don't know clouds at all

Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” is a perfect contrast. It’s a song that starts out with word paintings, three different highly poetic depictions of clouds. Next, the writer offers a more literal interpretation of clouds involving rain, snow, and blocking the sun – but it’s at this point that we suspect that the clouds of the song are actually metaphors for life’s obstacles or illusions that obscure truth and deeper knowledge. One quick verse in and we are already immersed in an impressionistic world of figurative language and interpretation. The chorus emphasizes the theme of the “Both Sides Now,” how meaning is hard to nail down in any definitive way, how truth changes depending on the angle of one’s perspective.

Could we ask for two more contrasting songs from these two confessional singer-songwriters? Could we have asked for better examples of their work as it relates to the two schools of songwriting they exemplify?

Joni would go on from this early point in her career, writing more and more conversationally, with masterful displays of rhythm and vivid imagery, but never completely leaving her impressionistic style, not that I’m aware of. And like Steely Dan, or Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell’s lyrics give us glimpses of real situations, but usually in fragments that we each have to put together in our own way, infusing them with meaning according to our own individual interpretations. And the metaphors abound in her songs, the river, the coyote, paradise, parking lots, the car on the hill, the circle game, the hissing of summer lawns. Her confessionals invite our participation through interpretation and ultimately, by either relating to her story or learning from it.

The confessional singer-songwriter movement that grew out of the folk music of the 60s and came to full flower in the 70s eventually receded, and when it returned revitalized in the late 80s, it had changed significantly. The metaphors were gone (with a few rare exceptions – I just thought of one, Paula Cole is not really singing about cowboys in “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone”). I do not mean to cast aspersions – the artistry of the period is off the charts (see Fiona Apple, Liz Phair, Tori Amos), the more direct language and imagery has power and certainly, the “page out of my diary” style that endures to this day is accessible, affecting, and resonant. And popular!

What’s important to note is that the two schools, Lyrical Impressionism and Lyrical Realism are similarly based in empathy. Both have value, but they differ in style. How lucky were we to see them both so expertly and graciously exemplified on that night at the Grammys?

yes Joni writes in a painterly way often, aye? and there's so much more.

interesting